At the Benito Juarez Sports Complex near downtown Tijuana, a woman walks past a tapestry of the Virgen de Guadalupe in the middle of the migrant tents on Dec. 16, 2018. Peggy Peattie for KPCC

The migrant shelter that’s been set up at El Barretal, an old concert venue on the outskirts of Tijuana, is a sprawling sea of tents.

The camp buzzes with activity. Men talk and play cards, gathered around boomboxes blasting cumbia. Women shake out blankets and fold donated clothes. People have set up makeshift vendor stalls, selling trinkets and gum to earn a little money.

There are thousands of hopeful asylum-seekers from Central America camped out in Tijuana, many with children, living in shelters or makeshift camps. It’s not clear how long they’ll remain at the border.

On Friday, the Trump administration announced that asylum seekers entering the country from Mexico, either illegally or “without proper documentation,” would need to remain in Mexico while their asylum claims are processed, even once they are interviewed by U.S. officials. The new policy clashes with the longstanding practice of not returning non-Mexican migrants to Mexico.

All around this shelter, there are children, walking alongside their parents or playing amid the tents. They are trying to make sense of their journey, their future. They are also just being kids.

At the El Barretal shelter in Matamoros, Tijuana, Ruth Reyes, 5, shows her mother a new doll she was given on Dec. 16, 2018. Peggy Peattie for KPCC

CAN’T GO BACK

Not far from the shelter entrance, three-year-old Monserrat played with donated toys in the tent that she, her four siblings, and their parents call home these days. She put a toy pot on a tiny plastic stove.

“I’m going to cook!” she shouted brightly in Spanish. “I’m going to cook FOOD!”

Just outside the tent, Monserrat’s mother Rosa Reyes smiled a tired smile and shook her head.

The Mexican government-run shelter serves two meals a day, Reyes said, but it isn’t much.

As winter settles in, families like these who arrived from Central America in hopes of coming to the U.S. are learning to live in limbo as they wait, unsure what their future holds. As for the kids, many are too young to fully understand why they left, and why they’re here.

Reyes says caravan or not, they still would have left Honduras. She and her husband Alexander left their country on October 13 with five kids in tow, ranging in age from 10 years to 10 months.

They had a stroller for the youngest ones. The two oldest, 8-year-old Ruth and 10-year-old Genesis, came all the way to Tijuana on foot.

“It was difficult, lots of walking,” said Ruth, the bubblier one of the two oldest. “Lots of walking, lots of running around, and we got sunburned – lots of sun.”

There are still blotches the girl’s arms where her sunburned skin peeled.

At the El Barretal shelter in Matamoros, Tijuana, Monserrat Reyes, 3, has her new dolls kiss, as she plays near her family’s tents with the toys she was given on Dec. 16, 2018. Peggy Peattie for KPCC

“Believe me, it would break my heart when they’d say Mom, I can’t stand the sun,” said Reyes, in Spanish. “They would say Mom, we don’t want to walk, let’s go home, let’s go back to Honduras.”

But they pressed on. Reyes says that’s because they can’t go back. She hasn’t told the kids exactly why – she says they’re too young to understand now.

“We were threatened,” she said quietly. “And they threatened my children.”

The couple had a small business, Reyes explains, a produce stand. To operate, they had to pay extortion money to a local gang back in San Pedro Sula. After countless shakedowns, they ran out of money. They were given a deadline to pay up. Tattooed thugs visited them, she said, making threats. Then the threats turned personal.

“They said…”if you don’t pay, one of your children will turn up dead,” Reyes said.

A few days later, they heard about the caravan. They packed up the kids and left.

They have no family in the US and no idea where they would live, Reyes said. But a few friends on Facebook have suggested Los Angeles, and that has fueled her dreams.

“Los Angeles must be beautiful, because even the name expresses it… Los Angeles, the angels, come from God,” she said. “I can imagine, it must be beautiful.”

But it’s harder convincing the kids. Asked if she wants to come to the United States, Ruth’s answer was a resounding “No!”

“I want to go back to Honduras,” she said. Then, seeing the disappointed look on her mother’s face, she fidgeted.

“I want to keep going,” she said reluctantly.

LIVING IN LIMBO

Just a few yards from where the family is camped, Ana Elia Valdez sees this kind of uncertainty and confusion among the kids there on a daily basis.

Valdez is with Save the Children, an international NGO that has a tent set up at El Barretal where kids can come let off steam with art projects and games.

“Their emotions are mixed up,” Valdez said in Spanish, as a group of kids next to her played Loteria, the Mexican game of chance. “At one moment you’ll see them sad, the other you see them happy, then restless, and sometimes they have a lot of aggression.”

She and other aid workers help provide emotional support, she said, allowing the kids to work out their feelings as they draw and play.

Valdez says living in limbo, uncertain what the future holds, is deeply affecting the kids and their parents.

Experts say that’s just part of it. These kids have endured layers of trauma, said Natalie Cruz, a psychologist at Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles. In recent years, she’s worked with many Central American migrant families who have made it to the United States and settled here. The kids have been referred to her, often through their schools.

These kids, like the kids in the camps, have already experienced layers of trauma, she said.

“They’ve got the violence that they may have witnessed in the home country,” Cruz said. “They’ve got the journey, which is, you know, for these kids, it’s been a pretty arduous one, they’ve…a lot of them walked for like a month. And now, they’re having to wait for an extended who-knows-how-long period of time before their parents can present themselves. So you’ve got a threefold thing going on.”

At the El Barretal temporary migrant shelter in Tijuana, Abigail Thompson Maldonado from Honduras, talks about the journey she and her husband and their three children made to reach this spot on Dec. 16, 2018. In the background are Luis Antonio, 9, and Alexandra, 11. Peggy Peattie for KPCC

As for parents, Cruz said, some may themselves be second-guessing their decision to head north with their kids. It’s a train of thought she’s seen in migrant families even once in the U.S., after experiencing the challenges of migrating and resettling and especially after enduring long separations as parents and children arrived separately.

“It is a constant question for them,” she said “Did I make the right decision? Did I make the right choice to migrate here? You know, my intention is to provide my child with a better life. But has it been worth it?”

Back at the camp, Valdez with World Relief said things are in flux: Families are moving in and out, or leaving for other shelters. Some are looking to go back to their home countries, or have already left. Others aren’t sure what they’ll do.

“I think (the children), as well as their families, are going through uncertainty right now,” Valdez said. “They have their American dream, but they don’t know what’s going to happen to them.”

A few tents away from the Reyes family, Abigail Thompson Maldonado was trying to stay strong as she camped out with her husband Julio and their three kids, 11, 10 and 6. It was a rough journey for them: Their youngest, 6-year-old Doris, suffered burns on her arm early in the trip when someone accidentally spilled a donated cup of soup on her arm.

She’s recovered, her mother said, but now at the shelter, the nighttime Tijuana temperatures have chilled the children, who are accustomed to the tropics.

“They’ve gotten sick,” Thompson Maldonado said in Spanish. “Sometimes, we can’t sleep because of the cold.”

But when the kids ask things like “when can we leave?” she tells them, “soon.”

“Soon we will get to the United States to work,” she tells them, “and so you can study.”

Doris, who says she dreams of seeing snow, takes it to heart.

“I’m going to be a doctor!” she shouted.

“We’re confident in God,” Thompson Maldonado said, “ that God will help us.”

At the Benito Juarez Sports Complex near downtown Tijuana, Maria Isabel Reyes, 40, center, stands amid the garbage and migrant tents on Dec. 16, 2018.

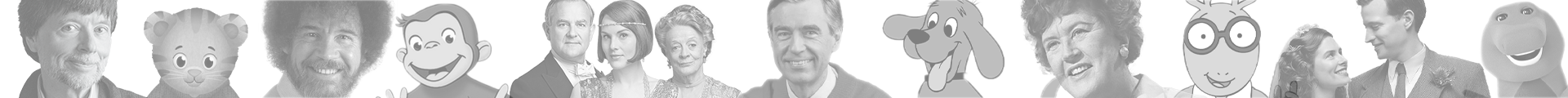

In Tijuana, Mexico, children members of the migrant caravan are learning to live in limbo as they move between shelters, settling in as much as possible to create a sense of normalcy, with help from NGOs, counselors and aid organizations. (Photo by Peggy Peattie) Peggy Peattie for KPCC

“WE DON’T KNOW IF WE WILL STAY”

Most of the migrants at El Barretal have taken a number, hoping that when theirs comes up, they can present themselves to U.S. officials at the San Ysidro port of entry and ask to be interviewed for asylum. Already before Friday’s announcement, it was unclear how long they would have to wait in Mexico, and there were no guarantees they’d be accepted into the U.S. The Mexican government has since said it will extend humanitarian protections to foreign asylum seekers whose cases are being decided by U.S. officials.

Still, for those already waiting in the camps, the new policy adds to their dilemma.

Some, like Maria Santos, are giving up.

Santos, from Honduras, and her family were camped far across town from El Barretal, in a makeshift tent city close to the border fence in Tijuana.

This unofficial camp sprung up outside the Benito Juarez sports complex, the site of an earlier migrant shelter, after that shelter flooded during a rainstorm and was closed.

Santos sat in front of her tent with Asli, her 9-year-old daughter. She smiled weakly as the little girl held up a Disney Little Mermaid costume, a donation from volunteers.

Santos looked exhausted. A growing pile of garbage bags sat a few yards from their tent. People could be heard coughing nearby. She said she can’t imagine going any further.

“We’re asking God to guide us,” Santos said in Spanish. “We don’t know if we will stay, or what we will do.”

At the El Barretal shelter in Matamoros, Tijuana, in one of the covered areas, migrants are happy to be out of the rainy plot in their original shelter at Benito Juarez Sports Complex near downtown on Dec. 16, 2018. Peggy Peattie for KPCC

Santos said they’d thought seeking asylum in the US would be easier, that they would be allowed to cross the border. She said they’d heard people say this in the caravan. “It was a lie,” she said bitterly.

Santos was with Asli at the camp, near the fence, when U.S. agents fired tear gas into Mexico during a border protest.

She recalled covering her daughter’s face to protect her as they choked on the gas.

“It was a bad smell, and my eyes watered when they threw those bombs,” said Asli.

Santos said the incident further shook their faith in the idea of continuing north.

Since then, her husband and their older son have found work here in Tijuana, in construction. They no longer see the United States as a feasible option.

Neither does Asli.

“Since they don’t let us cross, we’re going to stay here,” she said.

Her mother agrees. If they can find a place to live, she said, they’ll try to make a new home in Mexico.

The California Dream series is a statewide media collaboration of CALmatters, KPBS, KPCC, KQED and Capital Public Radio with support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the James Irvine Foundation.